Leaf 11

“All Night Long”: Eroticism in the Red Gallery

[Louise Bonnet, Patricia Ayres, D.H. Lawrence, Sidse Meineche Hansen, and Katje Sesb at Site Santa Fe]

In 1755, Felice Fontana—the collaborator of the great Italian anatomist Leopoldo Marco Antonio Caldani—was called by the Grand Duke of Tuscany to create a Cabinet of Physics and Natural History in the Pitti Palace. This Museum, as well as those famously opened in Vienna, Montpellier, Bologna, Paris, and London, constituted an allegorical encyclopedia of fleshy fantasies. None more famous than the shamefaced Adam and Eve, depicted sexually-aware after the Fall, or the not-for-the- cold-blooded “Anatomical Venus” who appears to have died during love-making. Elegantly adorned [or, rather, tantalizingly undressed] in Rococo fashion, the latter is displayed—throat gorged, tight double-strand pearl necklace, blonde wig with head thrown back—in a taffeta-lined rosewood case crafted by Clemente Susini. i

How does this silky material, the waxy-smooth slip of the flesh enticing the lover’s slide of hand, the pre-politically-correct feminine abandonment to voyeuristic desire, and the flayed open wound exposing moist generative organs encapsulating a tiny fetus, compare to the discursive contemporary installations?

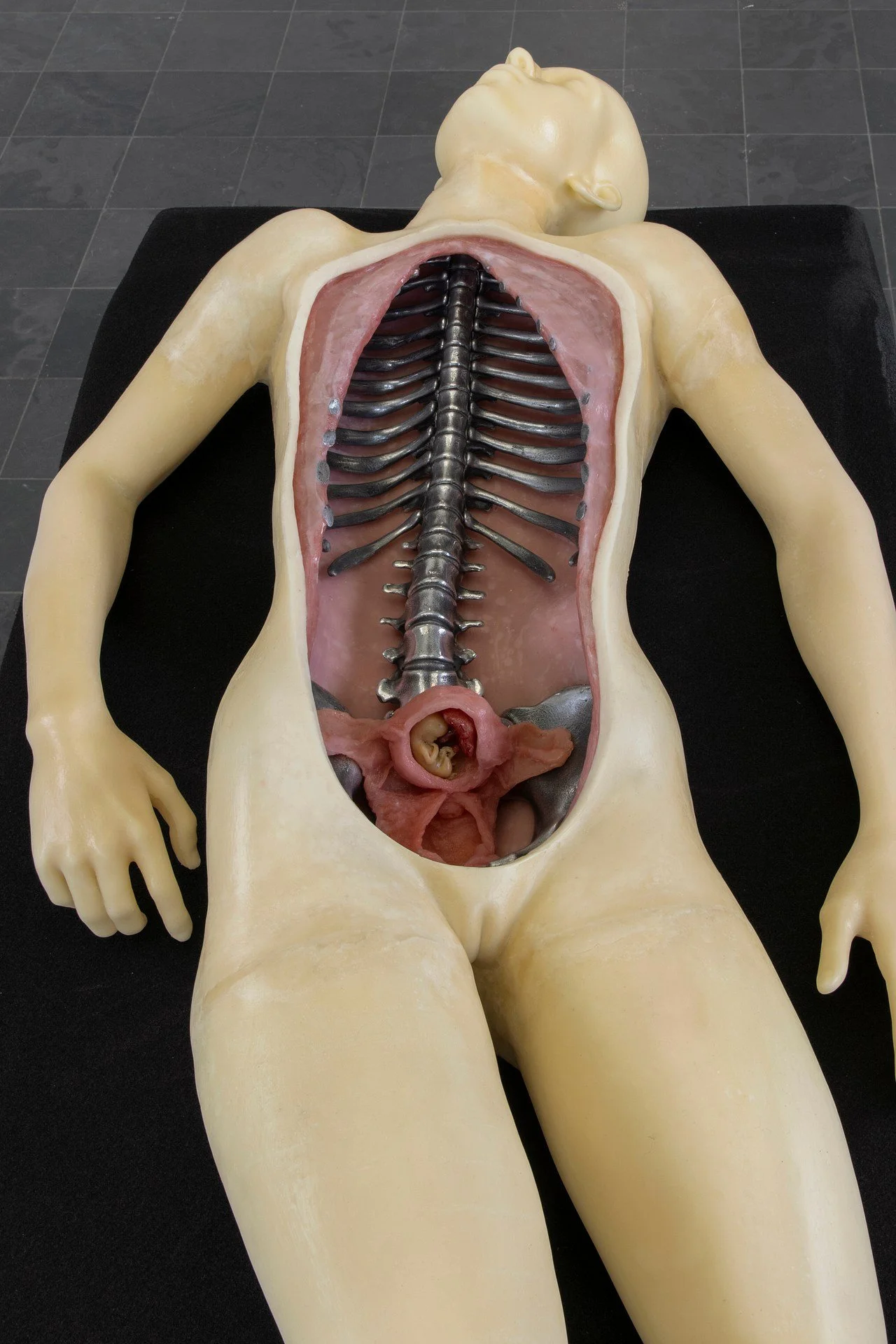

Clearly, Sidsel Meiniche Hansen has no empathy with, or sympathy for, Fontana’s carnal, affecting nude or her pleasurable pain. A beautiful woman, hidden inside the Italian’s dark studio and secular sanctuary, contrasts unevenly with an icy ceramic cadaver laid out on a slab. Unlike Fontana’s carefully-rendered organs, this body is fitted only with a generic metal ribcage and resin fetus –as if the presumed, and to be recalled, subtext is sufficient to get the message across.

However, if this is a visual argument presumably about sexual abuse, it requires accessories. As explanatory addenda, the Danish artist hangs a, shiny anchor-like bronze hook onto the wall [perhaps recalling pronged meat?] Add to this brusquely- juxtaposed scenario a suspended circular instrument -holder spelling out in crystal-clear letters: MISSIONARY. Are we then standing in a stripped-down “laboratory” whose bare “results” are, at first glance, hidden within a lurid red gauze rotunda? Paradoxically, this installation resembles neither once-breathing flesh nor the material realities of actual dissection but, rather, a digitally manipulated image asserting a prior verbally-made point.

Turning to the inept, sometimes ridiculous, small Rubenesque painted orgies and lascivious kissing couples by D.H. Lawrence is a relief. Nine paintings from a vanished era and given to La Fonda [secretly exhibited at the Hotel as “Forbidden Art”] are here, again, sequestered behind an alerting, peekaboo red curtain. Their spirited earnestness and physical enjoyment offer a happy—even mythical-- reprieve from commodity-status rhetoric. This is not because the British author and sometime Taos dweller achieves in paint the ecstatic pleasure and gut-wrenching release described in Lady Chatterly’s Lover or, my favorite, The Plumed Serpent. Rather, it’s because he attempts imagistically to convey fusive yearning, two longings straining to meet in the middle:

“In the closest kiss, the dearest touch, there is the small gulf which is nonetheless complete because it is so narrow, so nearly nonexistent. . . .Though a woman be dearer to a man than his own life, yet he is he and she is she, and the gulf can never close up. Any attempt to close it is a violation, and the crime against the Holy Ghost.”ii

While Lawrence’s presence pays tribute to a keen and wondrous erotic writer from the 1920’s and 30’s, Katja Seib’s three inexpert, large-scale paintings—scavaged from vintage photos she downloads on her phone—mystify. Why are they in this exhibition? Is it because they thematically allude to the past sexiness of smoking; fortune-telling as predicting the likelihood of romance; and the androgyne as gender-shifting as the moon when eclipsed by the sun?

Patricia Ayres’ cloth and cement phallus is a montaged tower composed of swollen buttocks, bandaged breasts, rubbed clitoris, and turgid penises whose convulsive entanglement is accentuated by ropes and straps. She lubricates the porous surfaces with fluids, using discoloring stain to join organic differences. Visually closest to Lawrence’s sensual prose, these body fragments erupt from floor to ceiling, achieving something of the writer’s impassioned order in upheaval. She captures not just the tumescence that connects partners but the impulse to reach out, dissolve, and meld with another.

Tellingly, Ayres orgiastic coupling is about parts not wholes: the post-post-modern impersonal personal. The titillated and titillating cleft or mound is essentially personless: physical arousal abstracted from subjectivity, divorced from a feeling individual, removed from a distinctive temperament and thrilled spirit. Louise Bonnet’s tumid parts, in turn, continue our current pictorial apotheosis of headless, legless, handless sexual dissection. Enlarged buttocks, balls, fingers, feet, breasts, nipples pleasure one another in epic feats of anonymous penetration or solipsistic masturbation.

Is this the new erotic? Or is it just the steady leak of dissociating online pornography and boredom into the imagining of intimacy? Covering the facing wall, Bonnet’s small paintings—mainly in fleshy red washes dwindling to cool blue—zero in on everything from the mechanics of foreplay to. the conceivable varieties of entry. These works underscore the larger question. The viewer zooms in on flowering vulvas, charged penises contemplating Venus Dentata, to ghostly child -birthing occurring between wet lips and membranes. We are hooked into ambiguity.