Leaf 12

Desert Floor: Order under Drift

[Corman McCarthy; Candace Lin,” Toxic Semiotics;” Dionne Lee, “Rock Drawings; Awa Tsireh, “Pueblo Indian Watercolors;” Ruyi Zhang, “Traces;”Eliot Porter, “Ornithological Geometries;”Vladimir Nabokov, “Spiral Speciation,” at Site Santa Fe]

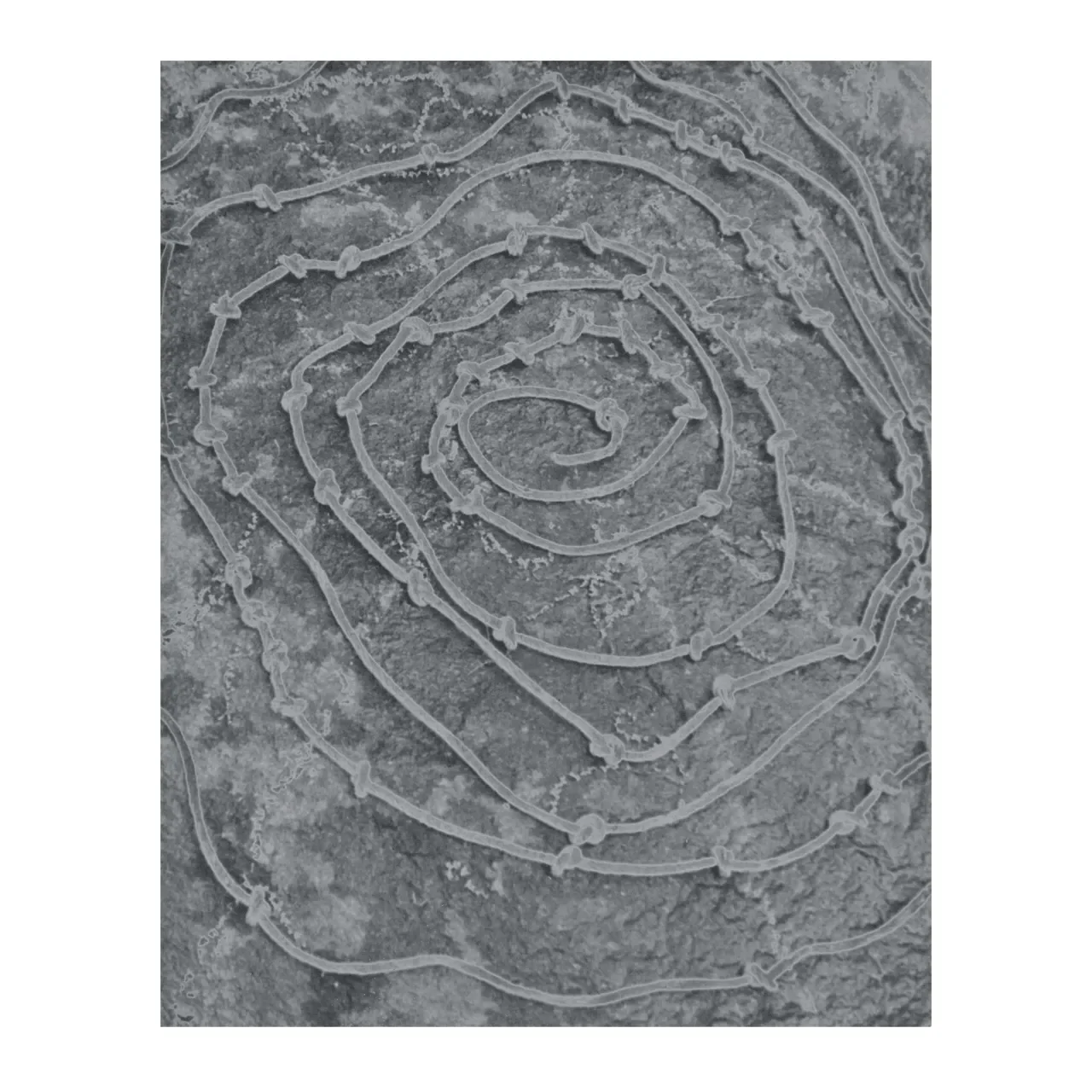

Dionne Lee, Untitled Rock Drawing VI, 2024, solarized gelatin silver print, 8 × 10″

from https://www.artforum.com/features/dionne-lee-portfolio-1234737000/

On the High Line Flyer jolting to Cheyenne, Willa Cather describes crossing the sagebrush “gray-and-yellow desert” which is “varied only by occasional ruins of deserted towns, and the little red boxes of station houses . . . in that confusing wilderness of sand.”i Dust, rocks, and fossils come alive in this apocalyptic landscape under the beating rays of the sun. No wonder abstract features, symbolic geometries, and metaphysical ideas achieve singular clarity in this burning setting. The Southwestern desert is where the telling pattern in stone or residue of ancient soil emerges and vanishes. But it is not alone.

Cormac McCarthy’s “The Kekule Problem” [2017] reflects on the nineteenth-century German chemist’s dream-epiphany regarding benzene’s primal ring structure. His essay –referred to in a placard placed near the entrance of SHoP Architect’s remodelled building --introduces one of the larger motifs in Site Santa Fe’s collage of works. Insight into the connection between an archetypal pattern-- the spiral cosmic snake or mythic ouroboros and the eternal return of an imagistic unconscious—is first awakened while standing in the lobby --bathed by an oil-painted glass window. Large oblong fish, arched mounds, and swirling black hole vibrantly spill into space.

This tidal wave of transcendental color resonates with McCarthy’s cracked- earth vision—offering the visitor a prefiguration of nature’s disassembling on view in several galleries. In Candace Lin’s video projection, “Toxic Semiotics,” the most eloquent visual feature [to this viewer] is the immobile bed of gleaming sand, raked into wind-waves and animated by flashes of colored images said to refer to the past practice of entombing nuclear waste in salt. This information is given in a difficult-to-understand “Djinn” voiceover leaving unclear why their brightness is reflected in an audience of ceramic cats.

This puzzle raises a larger issue, that of a growing number of artists’ needing to make their visual point verbally—a problem permeating many of Site’s installations where, for one, nature-as-artwork, often is accompanied by a soliloquizing speaker. Voiceover commentary, tends to be experienced separately, as didactic add-ons making a point that has not been instantiated or visualized in the work itself. [More about this in the next Blog.]

Similarly, around the corner, in Dionne Lee’s single-channel video, the speaker argues that the American landscape is “a site of conflicted belonging. . . the suppressed history of colonization.” But what she depicts, instead, in her compelling 2024 “Rock Drawings,” is the power exerted by erosion or catastrophe to make visible the environment’s and our psyche’s geometric absolutes: the spirals and organic marks left on sliced stone set against random pebbles.

This graphic work, displaying applied ephemera such as chalk, string, graphite, is captured in a small series of silver gelatin photographs. Their intimacy permits us to see and ponder the character of nature’s as well as the artist’s dwindling lithic remains as they become reconfigured with time.

What, by comparison, are we then to make of the hieroglyphics deposited by our recent architectural leftovers? Those invisibles now made visible through shattered concrete or rusting girders are the subject of Shanghai artist Ruyi Zhang’s assemblages of urban detritus—ruined cement, broken tile, fallen metal grids and grilles left behind on abandoned construction sites. Her installation captures our desperate search for meaning in emergent symbols disclosed by the disintegration of global cities. Rusted pipes arouse visual analogies with budding cacti; rebar “grows” into an amorphous and mutant substance; melting cast -iron lattice seems to redefine not only contemporary sculpture but suggest novel and potential ornament discarded alongside the desert floor of stark skyscrapers and bleak glass-box office buildings.

Will they be today’s machinic and technological counterparts to the serpent, snail, and whirlwind imagery found in ancient rock art symbols? The Zuni’s, for example, believed the spiral pictured “the search for the center”ii just as the secretive sand paintings of the Aboriginal dream walkabout indicates a spiritual journey. While our impersonal and chaotic fragments reveal unstoppable forces, might current architecture not transform this tossed waste into considered design?

If the long tradition of topophilia [love and attachment to the land ]--stretching back to antiquity and forward to the Romantics and beyond--is being erased by “the loss of this Wild Prospect,”iii perhaps, realistically, a new aesthetics is required. We already have the rarity syndrome. Witness Eliot Porter’s incredible stills made with a Kodak camera in the 1960’s and 1970’s that turn birds into singular and abstract works of art. They could be ritual performers in Awa Tsiren’s watercolors: the Piikani owl or raven trapped inside contoured solid colors. Porter similarly transforms the blue Woodhouse Jay into an artful design, into a sort of sapphire brooch pinned to the blue sky or set into forest foliage. In his highly-wrought photographs, the topaz Warbler with pleated wing becomes an expensive jewel as does the ruffed and flaring fan of the cockatoo.

This philosophy of preserving the precious singularity also colors Vladimir Nabokov’s [facsimile] diagrams, drawings, and notes minutely investigating spiral speciation, butterfly mimicry, and metamorphosis. Like the probing archaeologist, this literary taxonomist pays attention to gem-cut rectangular wing cells, the checkered fringe of wings, the opalescent tinge of one species that is “akin to moonlight” described in a language worthy of an ornamentalist. But is this a sustainable or even adequate answer to how our entangled world is developing? The question becomes: Is this absolutist view that nature is a precious gem to be singled out in an AI world where everything, it seems, can be duplicated sufficient to the shifting times? Do we not also have an obligation to include our ruined human-made desert into our re-imagined rebuilding?

i Willa Cather, “A Death in the Desert,” The Garden Troll [New York and Scarborough, Ontario: A Meridian Classic, 1961], p. 65.